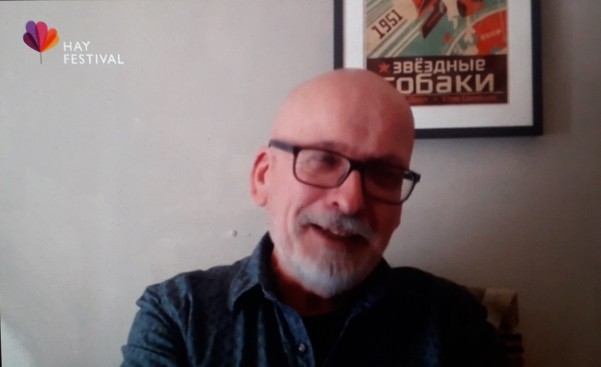

In conversation with Hay Festival director Peter Florence, Booker-Prize winning novelist Roddy Doyle talked Normal People, life under lockdown, Dublin pubs and his new book, Love (out on 23rd June in North America, October in the UK).

How was he doing? “Not too bad … I’m close to the sea. I can walk or cycle.” The pandemic had made him put aside a novel-in-progress which had been set in the present; instead he was trying to capture moments by writing short stories. Social distancing had a silver lining for professional eavesdroppers: nobody was whispering anymore, so he could hear “every conversation in Dublin” while out exercising.

Had the weekly pub evening been curtailed? Doyle still ‘met’ up with his friends via Zoom, but it wasn’t the same. “It took a long time for gaps in the conversation to feel normal. Utter silence … is this the best we can do? But we’re not in the pub … the thing I miss is the ability to mingle with people when you want to.”

What was it about dialogue that keeps him focussed? “I’m a Dublin writer … we talk a lot.” It was one of the best ways of getting a novel moving: “you’re gonna have to have people talking. There’s a pleasure in it.” Doyle realised he was “quite good at it” and that you could convey an inner life through dialogue. In his new novel “it takes these two men a very long time to get to the point.”

He talked about watching the TV drama series Normal People recently, which he found “very moving, very touching.” Doyle was particularly struck by author Sally Rooney’s treatment of sex, how aware, confident and considerate the young man’s character was. “Men of my generation were never prepared in that way. There was no sex education at the (Jesuit) Brothers schools.”

Florence: “The new book is about coming to terms with the past … an event that happened a long time ago. I’m fascinated by how you, as a teacher, now looks at your own generation … what is your subject going to be?”

“Old men coming to their peak,” replied Doyle. “I’m quite content with writing about people – men, mostly – who are getting old.” Re-reading books when you were older, it was interesting how different the experience was: “I’ve realised that people own their own memories;” two people’s versions of something they both witnessed at the same time could be very different.

Joe and Davy, the two characters in Love, “met at school in the 1980s. One went to college, the other one didn’t. In a short furious blast of living they share life for a year. They want to be part of Dublin pub life.” One emigrates to England but they keep in touch. Over the years they stop going out ‘on the tear’, but in the book they “drink themselves sober” discussing a woman they both met in their thirties. What’s she like now? What was she like then?

The novel is about their inability to share a memory. “These two men are clinging desperately to what they had. They love each other as friends and it’s very, very difficult for them to discuss this.”

“It’s the gaps you leave,” said Florence.

“Yes, that’s what I’ve done from the beginning,” said Doyle, “let the readers fill them in … I’ve never thought that reading was a passive activity.”

Florence: “the author’s voice … you know when a piece of writing is by Roddy Doyle. You somehow offer up the text to us …”

Doyle: “I’m more interested in the characters than myself … The Woman Who Walked into a Door is probably the best book I’ve written ‘cause I’m not in it.”

Questions from viewers:

Have you ever lost control of your characters?

Doyle said that his dialogue didn’t get out of control, but “I do try to replicate talk that goes off on tangents – football is a great one for men my age. Someone might mention abortion, then someone else talks about football.”

Do you orally work those lines?

Unlike fellow Irish writer Kevin Barry, Doyle didn’t “feel the need to recite lines out loud. The Commitments was written in a one-room bedsit … the walls were quite thin, so no … I really enjoy editing, hacking away with the red biro. In the absence of students I correct my own work … 6 out of 10.”

Are pubs connected with men’s mental health in Ireland?

“For better or worse, oh yes! They have been good for my own mental health – it’s very important if you lose someone to talk about it … but you also see drunks, people with the shakes … I’m not advocating it as a solution. But there’s a place for the Dublin pub. I’m 62. I don’t want to walk into a pub full of other 62 year olds, but I want to feel at home. It’s a retreat … a great place for chatting. If I get some good news or bad news I’ll put a book in my pocket and go off to the pub. Have one drink last one and a half hours … There’s nothing quite like it – and it’ll be a long, long time before we get it back.”

The post-lockdown idea of having to go online to book a 20 minutes slot in a pub was “devastating,” he said. “Luckily it’s funny.”

Doyle finished by reading an extract from his new novel, which sounded like a continuation of what he’d just been saying. It ended:

… Inside the pub was where life was. We entered it. We thought we’d stay there.